Although a complete analysis of the Hungarian sci-fi and fantasy genres would require extensive groundwork and would fill several books, I try to give a quick overview of what happened after 1989 in the field of speculative fiction for the benefit of non-Hungarian readers.

The article has appeared earlier on The World SF News Blog.

In the eighties there were already signs of the change that came in 1989 – in these years new authors appeared and started magazines (Helios, Metamorf) and anthologies (Analog) independent of the previously dominant Galaktika magazine and books. After the market became free, previous amateur and freelance authors flocked together to start publishing, and started series that welcomed Hungarian authors of the science fiction and fantasy genre. Notable achievements are the articles of Kornya Zsolt on fantasy that established the terminology of fantasy now still in use in Hungary.

The trends that were established during this period continue to influence works of fiction by Hungarian authors. The published foreign books determined the course of science fiction and fantasy in Hungary and the initial choices were determinative. In the nineties Hungarian authors even adopted English or French pen names and invented foreign personas to exploit the hunger of the audience for the new and foreign fantasy and sci-fi works. This tradition is still alive even though it is clear to the readers that the pen names belong to Hungarian writers. At the end of the eighties role-playing clubs and the publishing groups growing out from them take the place of the former anthologies (Benefícium, Valhalla, Cherubion)

Published science fiction included cyberpunk novels by William Gibson and film novelizations as well as a couple of space operas – serious hard sci-fi was overshadowed by adventures, although a few publishing houses did publish award-winning and genre defining works. The Galaktika Baráti Kör, the Möbius science fiction könyvek and the A sci-fi mesterei (Masters of Science Fiction) series by Móra were gems within this period. But even so, this decade was mostly the decade of fantasy (publishing works of Robert E. Howard, H. P. Lovecraft, Marion Zimmer Bradley and Jorge Luis Borges). Interesting how peacefully novels of quality like the books of Ursula K. Le Guin, Robin Hobb and David Gemmell and other previously untranslated classics from Zelazny, Andre Norton and Moorcock could coexist with role-playing literature and be labeled the same by readers hungry for the genre. Heroic and dark fantasy dominated the market with only a few urban fantasy and slipstream books here and there.

Small wonder that the new Hungarian fantasy and sci-fi writer generation also wrote mainly space opera and classic fantasy, and even though most of them were shadows of the works they imitated, some of them became classics within a few years. The new publishing houses flourished and offered opportunities to writers to experiment and find their voice. Many of them started their career in the nineties and matured and turned to more serious and personal themes. Hot shot writers of today were published first within these small workshops, like Szélesi Sándor (Anthony Sheenard), Markovics Botond (Brandon Hackett) and László Zoltán.

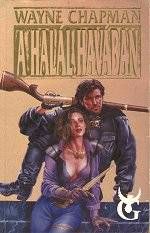

One of these pioneer publishers, Griff Books is especially important since it introduced two shared world brands that continue to be predominant even today: Káosz (Chaos), created by Nemes István (John Caldwell) and M.A.G.U.S., created by Gáspár András and Novák Csanád (collective pen name Wayne Chapman; after the first two books Wayne Chapman meant only Gáspár András).

One of these pioneer publishers, Griff Books is especially important since it introduced two shared world brands that continue to be predominant even today: Káosz (Chaos), created by Nemes István (John Caldwell) and M.A.G.U.S., created by Gáspár András and Novák Csanád (collective pen name Wayne Chapman; after the first two books Wayne Chapman meant only Gáspár András).

In the nineties, new publishing houses (Valhalla, Cherubion) started to publish books both from foreign and Hungarian authors – notable Hungarian novels include Ezüst félhold blues (Silver crescent blues), a noir story set in an alternative twentieth century, and the dark heroic fantasy Tier nan Gorduin-cycle (set in the fantasy world of M.A.G.U.S.) by Gáspár András; the Katedrális by Fonyódi Tibor (Harrison Fawcett), a time-travel adventure that became the foundation of the Mysterious Universe brand; the Kárpáthia books by Bán Mór and the Dark Mersant stories of Kornya Zsolt (Raoul Renier). The distribution model of Cherubion was interesting: forming a book club it sent science fiction and fantasy works (both translated and Hungarian) to the most remote parts of the country.

In 1989 Galaktika started the first Hungarian fantasy magazine, Fantasy, later called Atlantisz which introduced international fantasy authors and lived for 11 issues. In 2004 Galaktika magazine itself started anew and began publishing leading science fiction books by foreign and Hungarian authors, making it its point to introduce sci-fi short fiction from other nationalities.

During the nineties there were several attempts at publishing science-fiction and fantasy magazines – one of them, Átjáró started in 2002 and had 15 issues before closing. Role-playing games and fantasy had a strong bond, therefore RPG magazines (Rúna, Bíborhold/Holdtölte, Hasadék, Fanfár) also featured writings of foreign and Hungarian authors. For example, Csigás Gábor and Juhász Viktor, both dark fantasy and slipstream writers debuted in Bíborhold.

Currently we have no fantasy magazines only fanzines and anthologies. Our only horror magazine is called Fangoria. Science-fiction is better off: the monthly Galaktika magazine lives again and Új Galaxis and Avana Arcképcsarnok (published roughly twice a year) are both thematic anthologies welcoming new and amateur sci-fi writers.

Outside the genre, literary authors also used supernatural and fantastic elements in their works, some fine examples are A könnymutatványosok legendája (The Legend of the Tear Showmen) by Darvasi László (also translated to German), Bestiárium Transylvaniae by Láng Zsolt and Csillagmajor (Star Farmstead) by the late Lázár Ervin, just to name a few. Literary writers and fantasy writers did not mix, however, and the distinction dictated by tradition and the different approach to writing and literature resulted in completely different readerships.

The new millennium brought new publishing houses and new writers who are following the world’s sci-fi and fantasy trends, use the opportunities of the internet to market themselves and bring an unique and fresh approach into Hungarian genre writing. An interesting aspect of the Hungarian science fiction and fantasy writing are the writing workshops (Cohors Scriptorium) that started operating around 2000 and after the pioneers many others (Írókör, Karcolat) were founded. These workshops worked as the Western critique groups, and many new writers rose from their fold.

I mentioned that there are some shared world brands that were born at the beginning of the nineties and are still popular – the brand name is as strong an attraction as the name of the best writers, even though the quality of the books within the brands varies greatly. Most popular fantasy brands are Káosz, Cherubion and M.A.G.U.S.. Although there are space opera and sci-fi brands like Mysterious Universe, individual novels are more typical in the sci-fi genre, while most fantasy novels that are published today belong to one of the brands.

Emphasis on adventure and quick pacing is typical of most of the Hungarian genre works, although readers award with their attention and good critiques those writers who deal with serious themes and put good characterization and ambitious language forward. There are books and short stories that are interesting, novel, modern and unmistakably Hungarian – and there are more and more of them every year. The last five years have seen a new rise in interesting books – while previously adventure and entertainment were the call words, the newer novels try to reflect to social and personal problems and questions and are more somber in tone.

To sample the best of contemporary Hungarian sci-fi I would recommend László Zoltán’s Keringés (Circulation) and his short stories; Markovics Botond’s (Brandon Hackett) A poszthumán döntés (Posthuman Decision) and Isten gépei (Machines of God); and Görgey Etelka’s (Raana Raas) Csodaidők (Wonder Times) tetralogy.

Keringés searches the answer to overpopulation and global climate change by time travel; Markovics Botond explores the boundaries of being human and the way technological development exponentially grows into technological singularity; and Csodaidők is a poignant family history set into a turbulent political and religious future.

An interesting sample of contemporary Hungarian sci-fi and fantasy are the Hetvenhét {77} and Erato anthologies, published in the Delta Műhely series. Hetvenhét {77} offers short stories based on Hungarian fairy tales, while Erato includes erotic sci-fi and fantasy writings.

A side note: art is above the language barrier that Hungarian science fiction couldn’t breach, and several sci-fi and fantasy artists are working within the genre on international scale. Boros Zoltán and Szikszai Gábor won the Chesley Award in 2006, and are actively working on book covers and illustrations, as is Tikos Péter. Futaki Attila (comic book illustrator) has been published in French, and illustrated the Disney edition of The Lightning Thief.

Hungarian speculative fiction is getting interesting again.

Hozzászólások

[hanna további írásai]

Great article about science fiction and fantasy.I’m always interested in science fiction movies.

Unblocked games | Mario flash