Horror. One of the most controversial genre of movie history, and it looks like that it will remain the same. Most people say that bending (and breaking) the boundaries of visual violence is at its most significant in such pictures, and it is questioned whether how far the artists can (should?) go in depicting violence. What makes a horror movie of high standard? If it contains more than enough violence? Or if the amount is less, and the director uses the power of suggestion more often? In my short essay, I will attempt to answer these question – due to the nature of the topic, with the necessary subjectivity –, and, at the same time, try to select some of the most memorable pictures of the era for the readers. In answering the question I myself asked above, the year 1968 is a turning point, so the following text uses this date as a starting line. [Editor’s note: the original Hungarian article was published in 2011.]

At the end of the sixties, there was a strong sense of crisis in the American movie industry. The Vietnam War had the most effect on the US citizens at that time, and all the news footage of the media successfully drowned them with terrifying imagery: nothing could be depicted in the movies the same way as before. The decade of the seventies, on the one hand, brought a brand new method of imagery (due to the softening of censorship), and on the other hand, due to the negative public mood and the trauma of the war, most movies lacked a reassuring ending, realism became stronger, and somehow this was closer to everyday life.

It goes without saying that the horror genre profited for the softening of censorship, naturalism  and the amount of blood could be more, a lot more. But before anybody would point out – and would be correct to do so – that horror movies would not inherently become better just because there is more blood and the censorship is not so powerful anymore, I should mention one more very important thing: a new generation of directors took the stand in the seventies. This generation had (has) a natural talent to direct, to create a suitable atmosphere, and had an eye for proportion. Their body of work still has an effect in the American movie industry, and they are still copied (due to the lack of ideas and originality). Spielberg, De Palma, Scorsese, Altman, Romero, Hooper, Craven, Friedkin, Carpenter or Ridley Scott became ‘deciding factors’ in this decade. Since the appearance of this generation the number of newfound talents became lower with every passing decade. The members of this “list” all revolutionized something in the “horror” sense of the phrase – a style, the entire genre, or only one version of it (Scorsese could be the odd man out of these names, but he made a pure American exploitation movie – or, at least, it was intended as one – in 1972 called Boxcar Bertha).

and the amount of blood could be more, a lot more. But before anybody would point out – and would be correct to do so – that horror movies would not inherently become better just because there is more blood and the censorship is not so powerful anymore, I should mention one more very important thing: a new generation of directors took the stand in the seventies. This generation had (has) a natural talent to direct, to create a suitable atmosphere, and had an eye for proportion. Their body of work still has an effect in the American movie industry, and they are still copied (due to the lack of ideas and originality). Spielberg, De Palma, Scorsese, Altman, Romero, Hooper, Craven, Friedkin, Carpenter or Ridley Scott became ‘deciding factors’ in this decade. Since the appearance of this generation the number of newfound talents became lower with every passing decade. The members of this “list” all revolutionized something in the “horror” sense of the phrase – a style, the entire genre, or only one version of it (Scorsese could be the odd man out of these names, but he made a pure American exploitation movie – or, at least, it was intended as one – in 1972 called Boxcar Bertha).

Interestingly enough, the first horror-masterpiece of the decade, Rosemary’s Baby (1968) was directed by Roman Polanski, a non-American director. Allegiance with the Devil, the critique of the big city life, surreal and morbidly erotic feverish dreams – and an unforgettable Mia Farrow, whose haircut in this movie returned on several “copycats”. Night of the Living Dead by George A. Romero was also made in 1968, and also gave a powerful push to this trend. In the same year, the president of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), Jack Valenti, who held that position for two years at that time created the new rating system, and the first subject which was observed through this filter was a British Hammer-horror. The significance of the categories G, PG, R and X continuously strengthened as time passed, (and nowadays it is a major viewpoint for studios in terms of incomings and planning). In 1969, Midnight Cowboy, John Schlesinger’s drama got the Academy Award, in spite of the fact that it got an X-rating from the committee, which was mostly associated with pornographic movies. If nothing else, this fact gave a lot more courage towards the “toughness” of pictures in production at that time. Violence and naturalism found their way and legitimisation into mainstream, the underground spirit and methodology of the sixties appeared in the major studios (the “violence supervisor” on the set of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather is a well-known story), and the production of A Clockwork Orange and Straw Dogs in 1971 meant another important milestone.

Wes Craven shot one of the classic titles of the exploitation (a more grievous subgenre of horror, to tell the least) movies in 1972, The Last House on the Left. The story focuses on the torture and murder of two young girls, and the revenge which comes afterwards (see Jungfrukällan by Bergman). This picture stood out even from the new trend, so it was either heavily cut or completely banned – but today it is considered as a real ground-breaking piece with its sickening tone, characters, and its effective dream images (if only they would have left out those two policemen).

In the same year, American horror cinema received international recognition, thanks to Robert Altman’s Images (Susannah York, the female lead received a Palme d’Or). Altman, who was at his most energetic state, created an unforgettable psycho-horror by mixing blood, eroticism, and all the more surrealism, but the picture never reached a wider audience, thus remained some sort of forgotten masterpiece, unlike the big hit of the following year, which was directed by William Friedkin, who got all imaginable awards two years before. One can say that 1973 was the year of The Exorcist. Friedkin’s horror movie is perfect in all sense of the word, and found the balance between atmosphere, character building and sickening special effects (and received a handful of Academy Awards for these). A demon possessing an innocent child remains a favoured motif ever since, and although this storyline feels like it has been told a thousand times nowadays, Friedkin’s classic received several backlashes short after it was even made due to the varying standards of European prints, and topped it all with the movie’s utterly forgettable sequel in 1977. But there was an equally effective picture with the same central theme, and interestingly enough, it was made earlier. Directed by Waris Hussein, who later on became a television director, the 1972 movie The Possession of Joel Delaney – starring the great Shirley MacLaine! – had such a brutal ending (also focusing on violence against children) could give Stephen King the willies even decades later, who said that this movie could not be made today for the censors would not allow it.

In the same year, American horror cinema received international recognition, thanks to Robert Altman’s Images (Susannah York, the female lead received a Palme d’Or). Altman, who was at his most energetic state, created an unforgettable psycho-horror by mixing blood, eroticism, and all the more surrealism, but the picture never reached a wider audience, thus remained some sort of forgotten masterpiece, unlike the big hit of the following year, which was directed by William Friedkin, who got all imaginable awards two years before. One can say that 1973 was the year of The Exorcist. Friedkin’s horror movie is perfect in all sense of the word, and found the balance between atmosphere, character building and sickening special effects (and received a handful of Academy Awards for these). A demon possessing an innocent child remains a favoured motif ever since, and although this storyline feels like it has been told a thousand times nowadays, Friedkin’s classic received several backlashes short after it was even made due to the varying standards of European prints, and topped it all with the movie’s utterly forgettable sequel in 1977. But there was an equally effective picture with the same central theme, and interestingly enough, it was made earlier. Directed by Waris Hussein, who later on became a television director, the 1972 movie The Possession of Joel Delaney – starring the great Shirley MacLaine! – had such a brutal ending (also focusing on violence against children) could give Stephen King the willies even decades later, who said that this movie could not be made today for the censors would not allow it.

1973 also marked the beginning of a great series. Brian De Palma’s Sisters, a mixture of horror a thriller gained fame with its new, unpredictable structure. Inspired by Hitchcock’s movies, De Palma’s bloody, yet brilliantly written pictures continued even in the eighties, but then the director went on to do other types of movies. De Palma often marked as someone who cannot do anything but Hitchcock; well, in my point of view these assumptions have no basis, and movies like The Phantom of the Paradise (1974), which was written by the director himself and mixes the themes of The Phantom of the Opera and Faust into a horror-musical (!), and Carrie (1976), a great King adaptation prove my point.

1973 also marked the beginning of a great series. Brian De Palma’s Sisters, a mixture of horror a thriller gained fame with its new, unpredictable structure. Inspired by Hitchcock’s movies, De Palma’s bloody, yet brilliantly written pictures continued even in the eighties, but then the director went on to do other types of movies. De Palma often marked as someone who cannot do anything but Hitchcock; well, in my point of view these assumptions have no basis, and movies like The Phantom of the Paradise (1974), which was written by the director himself and mixes the themes of The Phantom of the Opera and Faust into a horror-musical (!), and Carrie (1976), a great King adaptation prove my point.

If we are talking about 1974, it means Tobe Hooper and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Purist would have banned Hooper’s work with no other basis than its title, but the funny thing is that the director opted for a PG rating because the movie “barely has blood at all, one, maybe two ounces”. The ground-breaking horror picture received an 18 rating from the BBFC (the British counterpart of the MPAA) only in 1999, up to that point (with very little breaks) it was completely banned. The justification of this “mercy”: „After lengthy consideration and careful reconsideration, we decided that the horror scenes of this movie cannot be taken seriously; times change and so do viewers’ expectations. It was evident that today’s viewers will not have any problem with scenes which shocked the moviegoers thirty years ago

Times change, but Hooper’s Texas did not, it remains as powerful as it was when it premiered. Its exemplarily shocking tone, sickeningly spectacular details, the mise-en-scéne which takes the smallest details and uses them with maximum effect, and the basic storyline (a group of young people gets into a brutally big trouble) which is still copied without any new ideas even today make this picture into an unquestionable American classic.

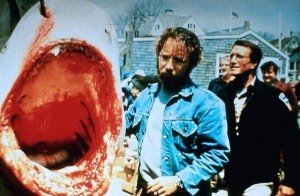

One of the most attractive characteristics of the seventies was the great variety in genres. This variety was present in the field of horror movies, too: exorcism, cannibals, mutants, zombies, animals, exploitation, religious themes, and so on and so forth. The limelight shone upon an animal horror in 1975, and showed the world the beginning of a great career. Jaws by Steven Spielberg also spawned dozens of copies and imitations, which may have been made with a bigger budget or in better conditions, yet did not even come close to the standards set by the original. Spielberg and his crew gave life to this movie from basically nothing in the editing room, since he went through living hell during the shooting: only those did not find the fake shark funny who did not see it. Yet the finished film swept everyone off their feet, and gave further evidence that human talent, the ability to put a movie together, and creativity are so much more important than anything else (in this case, even than special effects).

One of the most attractive characteristics of the seventies was the great variety in genres. This variety was present in the field of horror movies, too: exorcism, cannibals, mutants, zombies, animals, exploitation, religious themes, and so on and so forth. The limelight shone upon an animal horror in 1975, and showed the world the beginning of a great career. Jaws by Steven Spielberg also spawned dozens of copies and imitations, which may have been made with a bigger budget or in better conditions, yet did not even come close to the standards set by the original. Spielberg and his crew gave life to this movie from basically nothing in the editing room, since he went through living hell during the shooting: only those did not find the fake shark funny who did not see it. Yet the finished film swept everyone off their feet, and gave further evidence that human talent, the ability to put a movie together, and creativity are so much more important than anything else (in this case, even than special effects).

Many animals followed Spielberg’s Jaws: along came the bears, piranhas, bees, ants, dogs, whales, but all of them failed, and although some of them showed considerable qualities, and most of them had an exponential amount of blood than Spielberg, who remained faithful to the PG rating until 1993.

The spirit of The Exorcist returned in 1976, but the possessed Regan got denoted, and her place was taken by the satanic Damien in moviegoers’ nightmares. The Omen is a professional work in all senses of the word, a worthy counterpart of The Exorcist, and one of the few horror movies which have a truly memorable musical score (written by Jerry Goldsmith). By the way, it’s worth looking at the cast of characters of the greatest horror movies of the decade. They have a great number of names from the acting legends of the older generation (Gregory Peck, Max von Sydow, Richard Harris, George C. Scott, Melvyn Douglas, Robert Shaw, Piper Laurie, Richard Burton, Burgess Meredith, William Holden…), unlike today, for contemporary scary flicks are made as endless brands with a specific age group in mind, packed with young characters (who are the same age as the intended audience). This is another proof to the fact that this genre was taken more seriously in the seventies and was considered a lot more universal.

And horror still had a kitchen sink to throw at the end of the decade. Craven’s man-eating mutants (The Hills Have Eyes, 1971), Donald Cammell’s bloodthirsty computer (Demon Seed, 1977), or John Carpenter’s knife-wielding murderer (Halloween, 1978) received both great response and fandom. In the meantime, remakes and sequels made even more moneys, the Body Snatchers made a memorable return in 1978, and a certain David Lynch appeared. But the two biggest hits were delivered by – again – Romero and a fairly unknown English director, Ridley Scott. Romero’s second living dead-filled nightmare, Dawn of the Dead (1978) may be the sequel to his 1968 movie, but it’s a completely different picture. Using the possibilities of the decade, the special effects are even more gruesome, it has satire, nihilism, epic length: one of the greatest achievements of the decade, which brought blood and social commentary as close as possible. This picture started the greatest wave of zombie movies (especially in Italy), and put Romero back on the map again.

The sci-fi horror Alien, which brought along the revival of monster movies, could be responsible for even more copycats than Dawn of the Dead. Scott put his creature which lays its eggs into human beings, hatches and kills again on a spaceship, thus turning claustrophobia up to eleven. More to this, Scott’s movie broke the trend of man-centred Hollywood pictures, for Lieutenant Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) became the movie’s main character – a woman who did not even look likeable at the beginning. Alien became a huge hit, the fact that sequels are still made is more than enough proof, and almost everyone had an Alien-script written by the eighties (including a certain gentleman called James Cameron, but that’s another story). By the way, the movie was threatened with an X-rating (and it would have gotten it if the finale would have been shot as it was originally planned), but ended up not being such a big deal as Spielberg’s Poltergeist three years later.

The sci-fi horror Alien, which brought along the revival of monster movies, could be responsible for even more copycats than Dawn of the Dead. Scott put his creature which lays its eggs into human beings, hatches and kills again on a spaceship, thus turning claustrophobia up to eleven. More to this, Scott’s movie broke the trend of man-centred Hollywood pictures, for Lieutenant Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) became the movie’s main character – a woman who did not even look likeable at the beginning. Alien became a huge hit, the fact that sequels are still made is more than enough proof, and almost everyone had an Alien-script written by the eighties (including a certain gentleman called James Cameron, but that’s another story). By the way, the movie was threatened with an X-rating (and it would have gotten it if the finale would have been shot as it was originally planned), but ended up not being such a big deal as Spielberg’s Poltergeist three years later.

The nearly dozen American horror movies described above became classics with time, and gave filmmakers a sort of guideline on how to proceed forward. The American horror cinema flourished in the seventies; the best thing about it was that it was mostly original, and the directors’ chairs were occupied by people who had a new, unique perspective, and were not simple craftsmen. All decade had to train their all moviemaking talents, and this happened back then (from the eighties, when videotapes appeared and major studios took over, this progress unfortunately retreated into the background).

And to answer the question I myself asked at the beginning of my essay on what makes a horror movie good, blood or suggestive power, here is my answer: neither. In my opinion three things are required to make an outstanding scary movie, and these things can be fitted into collective concepts.

The first one is story itself. There has to be one which the creators want to share with the audience and want to tell them. A good story musters up interesting characters with who we can even identify with, or, to put it simply, we do not fall asleep when they appear. The scriptwriter is responsible for the story we see coming to life on the silver screen. As for the characters, their responsibility is shared between the writer and the actors portraying them. But for the third thing, atmosphere, the director (or, in rare occasions, the editor) can be held responsible. If there is no atmosphere, it’s the sign of no directing, then even a well-written story can be filmed as an uninteresting one, and even interesting characters will fall flat. These three factors must be present in all cinematographic genres, so this is why – in the case of horror movies – I would collect these with the word ‘fear’ (or startling, scaring, fright, as you like). If the aforementioned trinity comes together, then there is a good chance that what we are about to witness is going to scare us, and so the great work of art achieves its purpose. At this point, the question of the amount of blood and violence becomes irrelevant. If the director uses more blood and still manages to scare us, he still succeeded, and even if he uses less. If the finished work lacks even one of the things mentioned above, but tries to compensate this with gallons of tomato juice, the audience will probably has to face boredom instead of terror after a while.

The decade I analysed in my essay depicts good examples on both – bloody and bloodless (R vs. PG) methods which lead to great horror movies. At the same time, this decade could be the first one which had the opportunity that the bloodier, more graphic motion pictures were no longer bound by rules, the limit was, so to say, the open sky, and the artists’ freedom could flourish with the growth of the audience’s receptivity.

In the next part of my analysis, I wish to examine the same genre in the following decade, but in the Old Continent, and it will become clearly visible that the contemporary moviemakers of our continent – just like their American counterparts – often reached this final frontier and made an even greater sport from bringing down the still-existing genre limitations, both in the sense of storytelling and the depiction of violence.

The article was written by Péter Brányi, and translated vy Ferenc Benkő.

A cikk magyarul az alábbi linken olvasható: http://sfmag.hu/2011/02/01/az-amerikai-horrorfilm-a-hetvenes-evekben/

Trivia:

- Rosemary’s Baby continued in the form of a novel in 1997, written by the original’s author, Ira Levin.

- The popularity and effect of the aforementioned films is shown by the fact that almost all of them were remade, and many of them spawned several sequels (like Jaws or Night of the Living Dead).

- John Williams showed his talent in more than one of the pictures analysed above: he composed the music for Images and the first two shark-centered movies. By the way, he received a Golden Globe-, BAFTA- and Academy Award for the score of Jaws. This is one of the most minimalist (using only E and F sounds), yet one of the most effective movie soundtracks.

Hozzászólások

[cikkbot további írásai]